Life Expectancy: A New Wrinkle for Equal Opportunity Policy

Image credit: Government Accountability Office

Image credit: Government Accountability Office

Are differences in life expectancy something we ought to account for in equal opportunity policies? Although this is not often discussed in the literature, my intuition is that the answer is yes. Furthermore, it is not merely a hypothetical issue—advances in medical technologies have sharply mitigated the great leveller, but only for those who can pay.

The Plague of Justinian (541–542), the first known pandemic on record,1 the Black Death in the fourteenth century, and the 1918 influenza pandemic are all evidence of infectious disease that did not discriminate much between king and pauper.2 Life expectancy was, accordingly, near 30 years in all regions of the pre-modern world.3 Although things have improved globally, even today, “infectious diseases remain the major causes of morbidity and mortality in much of the world.”4 While the average individual in the United States now lives much longer—thanks in large part to antibiotics, immunizations, and public health measures—there is still large inequality of life expectancy. For example, life expectancy at birth for males in 2010 in McDowell County, WV is 21.1 fewer years than for females in Marin County, CA (63.9 and 85.0 years, respectively).5

What does this mean for equality of opportunity? Imagine that Jane and John have exhibited in equal amounts whatever it is that you think is important to equal opportunity—e.g., hard work, merit, talent, etc. After using their equal opportunity and their equal basis to obtain whatever good is important to equal opportunity—e.g., resources, welfare, jobs, college admissions, etc.—they in fact have that good in identical amounts. Next, John dies at 65 years old and Jane dies at age 75. Does this matter to equality of opportunity?

If you think that the purpose of equality of opportunity is opportunity for welfare, you might suppose that Jane, living an extra ten years of a life worth living, has gained an edge on John. If they had each enjoyed 100 units of utility by the age of 65, and then Jane enjoys five more units, their equal basis has led to unequal benefits.

If you think that the purpose of equality of opportunity is income, you might suppose that John would have no cause for complaint. Yet, you might also reassess your commitment to income, per se, and decide that there is something valuable about Jane’s extra ten years and that this something is properly connected to the reasons you support equal opportunity in the first place.

For both of these scenarios, a simple way that we might make a transfer between Jane and John that would help them enjoy equal amounts of the good in question is to transfer money from Jane to John. There are some puzzles here, however. Imagine that one day there are some humans who are going to live for only 30 years, like our pre-modern humans, while others have access to super-technologies that allow them to live to 300 years. They each earned \$100,000 in the market and the first consumes that in their short lifespan while the latter must live a life of penury in order to ensure this same amount lasts for ten times longer. On top of that, we then tell this super-wizened individual that they need to transfer resources to the short-lived, making their life even poorer. Have we made the right adjustment—is an extra 270 years of life at ~1⁄10 the standard of living the proper bargain?

Another puzzle is that, of course, we do not know ahead of time exactly when Jane and John are going to die. While we might expect that John will die 10 years earlier than Jane, how could we possibly equalize their benefits without knowing? Would we instead require a system that adjusted everyone else’s benefits each time a member of the population died?

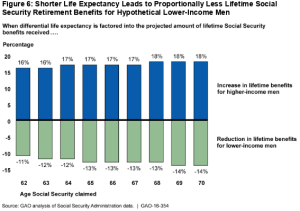

Yet another puzzle is what to do about benefits structured like Social Security? Above, Jane and John had resources that they needed to decide how to allocate to their present and future. Social Security payments, instead, are an annuity—specifically, a lifetime guaranteed annuity. In such cases, we can measure the financial flow of nominal dollars and easily see that Jane received more Social Security benefits than John. Moving back to the real world, the Government Accountability Office recently reported that high-income men tend to receive 18% more benefits, and low-income men 14% less benefits, than they would if they each survived to the same average age.6 This makes Social Security more regressive than a simple analysis of monthly benefits would suggest. Furthermore, as the Office points out, a policy change that some are discussing—raising the retirement age—will likely have a greater negative impact on low-income earners.

Although the life expectancy puzzle is difficult to unravel, it does seem to me that those with shorter life expectancies ought to receive some extra compensation if they have put in an identical amount of the equal opportunity basis. Nonetheless, my mind is not quite made up and I’m curious to see what policymakers do about this puzzle.

- McNeill WH. Plagues and peoples. New York: Bantam; Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc: 1976. ^

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45714/ ^

- https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy ^

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45714/ ^

- http://www.pophealthmetrics.com/content/11/1/8/abstract ^

- https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/676086.pdf ^